Quality Areas for study programmes in higher education

-

Purpose, target group, background and history

Purpose and target group

Higher education institutions are responsible for the quality of their educational portfolio. NOKUT’s role is to ensure society’s trust in the quality of higher education through accreditations, reviews, evaluations, relevant information on the higher education sector, as well as quality enhancement activities. The institutions, NOKUT and society thus have a demand for a definition of quality in higher education in order to evaluate, discuss, develop and control quality. This is underlined by Stensaker (2014) who states that the concept of quality is meaningless in itself, but rather must be divided into measurable parameters: “In order to make sense of the concept of quality, we have to relate it to something else.” (p. 4–5, our translation). (1)

Quality areas for study programmes in higher education are those quality areas we see as crucial for quality in higher education. A good study programme ensures that its students achieve the learning outcomes within the given time frame, while meeting the demands of society and working life. A good study programme is also expected to ensure the Bildung aspect. By taking the format of “study programme” as point of departure, we focus primarily on bachelor’s and master’s programmes, six-year professional studies and PhD programmes, yet do not exclude other relevant study offers. Discussing quality areas can also be of relevance for continuing education, as quality areas relate to legal requirements that apply to all study offers in higher education.

It is important to underline that the institutions should define relevant quality areas themselves. In other words, it is possible to take into consideration institutional characteristics, local quality cultures, and teaching and learning traditions within different disciplines.

This paper is written for both higher education institutions and NOKUT. Target groups at higher education institutions are staff working with educational quality, including leadership at different institutional levels and student representatives. The paper can also be of relevance for staff and students interested in the topic. For NOKUT internally, this paper is of relevance when considering how we define quality in higher education, and taking it is point of departure for formulating questions in evaluations and national surveys.

The views presented in this paper stem from different types of knowledge and experience, and we were required to select those carefully. Our knowledge base is composed of reports, policy documents and research, but also stems from our analyses, reviews, accreditations and our work with official rules and regulations.

Background and history

The idea of perceiving educational quality as the sum of all factors from different quality areas is not new and has influenced NOKUT’s approach to quality since its establishment. The first attempts to define quality areas in Norwegian higher education have been made in the 1990s by the Commission on Study Quality (1990) (2), which divided the concept analytically into:

– Structural quality (resources, rules, structures)

– Admission quality (previous knowledge, etc.)

– Program quality (teaching, curricula, exams)

– Outcome quality (learning outcomes)A report by the Norway Network Council (3), NOKUT’s predecessor, presented three additional areas:

– Teaching quality

– Relevance quality

– Governance qualityAt the same time the concept of study quality was replaced by educational quality.

In NOKUT’s first version of “Quality Ares for study programmes in higher education”, we defined eight quality areas:

- knowledge base

- learning trajectory

- start competence

- learning outcome

- educational competence

- society and working life

- learning environment

- program design

Internationalization was an integral part of each of the eight quality areas. In this paper we made changes about which areas we define as quality areas and how we describe them. When former concepts have been replaced, it doesn’t imply that they have become outdated, but that there is great variation in how quality areas can be defined and described. One example is found in the white paper “Quality Culture in Higher Education” (2016–2017) (4), which presents “five factors for quality in higher education”:

- good framework conditions

- educational leadership & community

- pedagogical competence

- teaching and assessment to encourage learning

- student engagement

(1) Stensaker, B. (1/2014). Kvalitet i høyere utdanning: behov for en mer nyansert debatt. Forskningspolitikk, Kronikk, s. 4–5.

(2) Studiekvalitetsutvalget (1990). Studiekvalitet: innstilling fra Studiekvalitetsutvalget. (F2898). Utdannings- og forskningsdepartementet. Norgesnettrådet (1999).

(3) "Basert på det fremste …?": om evaluering, kvalitetssikring og kvalitetsutvikling av norsk høgre utdanning: vurderinger og tilrådninger fra arbeidsgruppe nedsatt av Norgesnettrådet. (Volumer 2-1999 av Norgesnettrådets rapporter, ISSN 1501-9640).

(4) Meld. St. 16 (2016–2017). Kultur for kvalitet i utdanningen. Kunnskapsdepartementet.

-

About the model

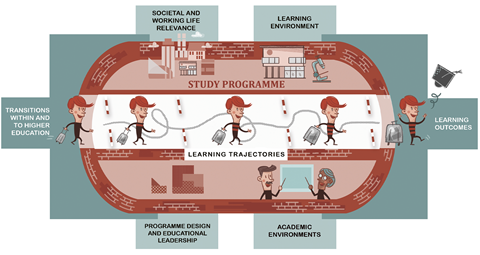

The quality areas in our model are:

– Transition within and to higher education

– Academic environments

– Program design and educational leadership

– Learning environment

– Societal and working life relevance

– Learning outcomesThese areas can be understood separately but also in relation to each other. All areas emphasize one dimension we think is crucial for the educational quality of a study program. In the following, we will describe study programme as analytical unit in our model. We also want to highlight how study programmes relate to other levels in the institution and to society in general. Finally, we will outline how higher education facilitates for knowledge development and good learning environments.

The study program as central unit in our model

NOKUT’s approach towards educational quality is to focus on study programmes, as we prioritize student learning. This prioritization becomes visible through the Regulations on the supervision and control of the quality in Norwegian higher education, our periodic reviews of institutional quality assurance practices, the National Student Survey, and other evaluations and surveys we conduct. Study programmes are at the centre in both the regulations and in our activities.

The Regulations on the supervision and control of the quality in Norwegian higher education refers to educational provisions, which cover the whole spectrum of study programmes at an institution.

While the students and the study programme are central in our model, the quality areas, which we present in this document, are embedded in the institutions. Quality work stems from the institutions overall quality system, which regulates how quality work is conducted. Local quality work at each study programme is equally relevant and presents an important source of information about the overall situation for quality at the institution.

In this document we understand quality areas from an individual perspective, a collective perspective, and as interaction between these two perspectives. An individual perspective on quality work focuses on how individuals perceive and contribute to the quality of a study programme. A collective perspective emphasizes how several actors create educational quality, and how different contexts and perceptions on quality create diverse quality cultures. The concept of quality has different meanings for different actors in the “quality process”.(5) Therefore co-creation and collaboration between different levels and different competencies at the institutions is needed to achieve good quality work.

The point of departure for our model is NOKUT’s mandate and activities, placing the study programme at the centre of this model. This focus means in return that important aspects of higher education in Norway receive less attention in this model. This concerns, for instance, how higher education contributes to social mobility, its accessibility for different parts of the country, and the institutions’ role in ensuring national and regional demands for competence and development. NOKUT would like to stress that these present important aspects of quality in Norwegian higher education, which are related the overall sector’s and the institutions’ role in society.

Knowledge development and learning communities

Higher education must be based on state-of-the-art research, recent scientific and artistic innovations, and experience.(6) Knowledge is thus in a constant change of state and subject to new insights and experiences, which are debated and reviewed continuously. Academic fields and students are both part of this ongoing process through their involvement in learning communities. A strong academic field provides students and staff access to different types of research, innovation, knowledge, experiences, research methods, research models, pedagogical methods and learning activities. A well-functioning learning community includes students actively in developing academic disciplines and makes them co-creators in establishing academic-, learning-, and quality cultures.

Student learning is at the same time not limited to a specific study programme or study place. It is in exchange with others that we learn, and this process can take place anytime and everywhere – through informal activities at the study place, students’ own learning activities, at an internship or study exchange at home or abroad, or in other contexts. Similarly, learning opportunities for academic staff is not limited to their disciplines and working environment.

A learning community consists of individuals. A pedagogical term that describes an individual learning process, is learning trajectory. A definition of learning trajectories can be “the learning processes that take place through our professional lives; our ways and methods to create meaning across the social experiences we make in different contexts.” (our translation).(7) In light of this definition, learning trajectories are dynamic and across different contexts, and are shaped through interaction. This means that the learning trajectories of the individual are linked to learning communities of which the individual is member. A main feature in this respect is that learning trajectories do not follow a specific goal, that they cannot be prescribed, and that different types of learning trajectories exist, which can be a way in or out of a learning community, or across them.(8)

In an educational context one can also refer to institutional learning trajectories.(9) The point of departure for institutional learning trajectories are the institutions’ objectives for student learning through their study programme descriptions and curricula. These objectives also include possibilities for student mobility, which contributes to shaping different, individual learning trajectories.

Both individual and institutional learning trajectories have relevance for student learning. In our model, learning trajectories together with study programmes, form the centerpiece of our model.

(5) Norgesuniversitetet (1/2015). Digital tilstand 2014.

(6) Jf. universitets- og høyskoleloven § 1-3.

(7) Wittek, L. & Bratholm, B. (2014). Læringsbaner – om lærernes læring og praksis. Cappelen Damm Akademisk.

(8) Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice. Learning, Meaning, and Identity. Cambridge University Press.

(9) Dreier, O. (2003). Learning in personal trajectories of participation. I N. Stephenson, H. L. Radtke, R. Jorna & H. J. Stam (Red.), Theoretical Psychology: Critical Contributions (s. 20–29). Captus University Publications.

-

Quality Area: Transitions within and to higher education

How does NOKUT define transitions within and to higher education?

For NOKUT transitions within and to higher education are about

– Start qualifications

– Admission quality

– Start of studiesThe preposition “within” in this context includes all transitions in higher education, such as moving from a bachelor to a master programme, from a master to a PhD programme, from a bachelor programme to continuing education, and other transitions. These transitions can happen at any given age. The preposition “to” describes the transition into higher education, which happens for most of the people after completing secondary education at a young age. In comparison, NOKUT’s sister organization QAA Scotland has conducted a project focusing on the ways of students into, through and out of their studies.(10)

Start qualifications consists of the knowledge, skills, and competencies the student has by entering a study programme. It also relates to the student’s motivation, attitude and experiences concerning his/her disciplinary area and study situation in general.

Admission quality consists of the institutions’ quality assurance procedures on the qualifications and start capacity of the applicants.

Admission quality can be ensured through specific entry requirements and exams.

Start of studies is about how an institution welcomes new students taking up their studies. This includes information about the respective study programme, time schedules, social and academic activities, as well as mentoring and supervision.

Why are transitions within and to higher education a quality area?

Transition can be challenging at any study phase. The Norwegian principle of “free education” makes it possible for everyone to study. The number of people who wish to take up an education is growing constantly, leading to increased competition on study places. Application numbers are rising as well as the number of first-time applicants per study place. The overall student population is hence more diverse than before. These issues can have relevance for the start qualifications, admission quality, and start of studies, but also for the student’s motivation, their learning, and drop-out.

Start qualifications is a relevant quality aspect in every education and at all levels. The way start qualifications of the students is taken into account, however, depends on whether it concerns a bachelor programme, master programme, PhD programme or continuing education.

To ensure high admission quality, institutions spend time and resources on information and guidance on study programmes and admission procedures, and possibly on various necessary pre-courses. Many institutions work intensely with student recruitment to attract motivated and qualified applicants.

The setup for the start of studies varies between the different study programmes. One should keep in mind that the students differ in age and life circumstances. One should also consider that students may have taken former education at other institutions or in another country. One key element in start of studies is thus culture. When students begin their studies at an educational institution, there is an exchange between the existing culture of the institution and the study programmes, and the former experiences of the students.

How to work on transitions within and to higher education

All institutions work continuously with targeted recruitment and providing comprehensive information about their educational provisions, and solutions are often context dependent. This applies also to measures for social inclusion, such as orientation weeks and arrangements by student organizations, which are common at most institutions. A concrete example for social inclusion is First Year Experience, which is a model for start of studies and based on experiences from the US higher education system.

At the same time, being part of an academic community is also important. One has to learn to be a student, learn how to study and immerse into academic thinking and the specific culture and tradition of the discipline and the institution (find more information on the students’ relationship to academic disciplines under “area of studies”)

-

Quality Area: Academic environments

How does NOKUT define academic environments?

In NOKUTs view it is the academic staff and their expertise that forms the academic environment.

The points of departure for academic environments are collective knowledge and collaboration. When addressing academic environments in higher education, NOKUT refers to the academic staff at universities and university colleges that work directly and consistently with the development, organization, and implementation of educational programmes. Academic environments present a key element in the knowledge base for educational provisions and ensure education of high quality as well as contribute to innovations through research and development activities.

The regulations for academic environments are specified in NOKUT’s Regulations on the supervision and control of Norwegian higher education education and contain a number of minimum requirements. These apply to the size of the academic environment, its stability, the staff’s pedagogical competence, as well as research capacity and networks. All these factors must be aligned with the particular characteristics of the educational programmes. The regulations allow for measuring and assessing an academic environment as a separate organizational unit, which will be assessed against the minimum requirements in the regulation.

Pedagogical competence is a specific element in the overall competence of academic staff and is about the teacher’s ability to promote student learning. Together with their colleagues, teachers are expected to describe, justify, plan, and discuss their teaching and education based on research on teaching and learning. Pedagogical competence implies also to enhance educational quality at study program level and to further development own teaching practices.

The definition of pedagogical competences has changed over time. In 2015, Universities Norway (in Norwegian "Universitets- og høgskolerådet (UHR)") developed guidelines for how pedagogical competence can be interpreted, which was referred to as “basic competence in university- and university college pedagogy”. Central elements were the organization and implementation of teaching, as well as the assessment, evaluation, and development of own teaching practices.

Given the increasing attention for student learning and educational quality, the term pedagogical competence has changed its character. We observe a broader and more collegial understanding of the concept, and what is expected of a teacher. This has also become visible in UHR’s definition of pedagogical competence. Since 2018, UHR links pedagogical competence to knowledge about policy papers for higher education, assessment and documentation of own practices and innovative thinking. Some of these elements have also become visible in the current regulations. NOKUT’s regulations states that an academic environment must have relevant pedagogical competence. In the Ministry’s regulations on appointment and promotion in teaching- and research positions, pedagogical competence is a central requirement in all positions.

Why do academic environments comprise a quality area?

The academic environments are of great importance for educational quality and a prerequisite to research-based education. There is no recipe for how an academic environment should be composed, but it should be relevant for the study programme profile and will therefore vary. It is essential that an academic environment consists of different competencies, which together contributes to academic development and makes it possible for student to achieve their learning outcomes.

Pedagogical competence takes Scholarship of Teaching and Learning as a starting point. This line of thinking is also connected to schemes such as excellent teachers and excellent education. In the white paper “Quality Culture in Higher Education” (2016–2017), pedagogical competence was highlighted, and it was suggested that pedagogical and academic competencies should have equal status.How to work on academic environments

The academic environments

Collaboration

In order for a good academic environment to have impact on study programmes, the persons within the environment must collaborate. A literature review by the Norwegian reserach institute NIFU from 2019 (11), emphasizes the need for an academic community among the teachers, independent of the size of the community. Discussing educational issues demands that the community has developed arenas and that there is good educational leadership.Students’ connections to the academic environment

Students are connected to the academic environments in different ways. Through lessons, they obviously meet different teachers and can access different kinds of knowledge. They also have the possibility to participate in the academic community this way, and sometimes they can even contribute to the development of different knowledge bases. The key for making this happen is that the academic enviromnet is available to the students.Pedagogical competence

Development of pedagogical competence and quality culture

Working on the pedagogical competence of the teachers within an academic environment means to ensure that everybody who is teaching has basic skills and that they also get the opportunity to develop these skills. Institutions may solve this with different kinds of measures, for example through pedagogical course, qualification schemes, peer review of teaching, seed funding, awards and merit schemes for outstanding teachers.

(11) Elken, M. & Wollscheid, S. (2019). Academic environment and quality of education. A literature review (Working Paper 2019:1). Nordic Institute for Studies in Innovation Research and Education.

-

Quality Area: Programme design and educational leadership

How does NOKUT define programme design and educational leadership?

Programme design is about the integrity of the courses of a study programme and the general learning outcomes for the programme. A core concept here is “constructive alignment” (11). Educational leadership is about the governance of study programmes and study portfolios, and is typically anchored in good programme design, quality work and experience-based development.

Why do programme design and educational leadership comprise a quality area?

Programme design and educational leadership are a quality area because of their importance for the governance and development of study programmes. It is expected that both concepts will contribute to an overall high quality study portfolio of the institution. Both concepts have been high on the agenda since the Quality Reform of 2003, with the overarching goal that students are able to develop a holistic understanding of their study field. For this reason, the white paper “Quality Culture in Higher Education” (2016–2017) states that institutions must consider multidisciplinary and innovative aspects, and a holistic view on study programmes and its contents, that transcends institutional boundaries. The white paper also stresses the importance of good educational leadership, that prioritizes educational quality and develops visions and ambitions for the respective institution in that study area.

How to work on programme design and educational leadership

Programme design and educational leadership is taking place in collaboration between scientific staff, students, student representatives, institutional leadership, educational leaders, administration, society and working life, alumni and other stakeholders on a local, national and international level. Programme design is for many institutions a cyclical and systematic task. In practice, this takes places through study programme and course development, which must consider, amongst other things, learning outcome descriptions of national qualification frameworks. Exchange of knowledge and experience between different (institutional) levels is of importance for educational leadership, as well as involving students in this task. Courses and incentive schemes (e.g., excellent teaching) can stimulate the further development of educational leadership.

(11) Biggs, J. and Tang, C. (2011). Teaching for Quality Learning at University (4th ed.). Society for Research into Higher Education & Open University Press.

-

Quality Area: Learning environment

How does NOKUT define learning environment?

Learning environment is the sum of all the parts that are of relevance for students’ learning, health, and well-being. This can include physical, digital, organizational, pedagogical, and psychosocial aspects.

Why is learning environment a quality area?

A good learning environment can be considered a precondition for high study quality. It matters for students’ learning processes and well-being, for student involvement and for students’ ownership to learning.

How to work on the learning environment

Working on the learning environment includes av variety of tasks, and one must consider the variety of the student body (e.g., full-time students, international students, students with children, etc.) and the specific needs of different study programmes at the institutions.

The university board has the overall governance responsibility for the students’ learning environment. Every institution must also have a learning environment committee, consisting of students and staff equally. The committee and university board shall ensure a good learning environment in terms of the students’ health, safety, and well-being.

Learning environment as a quality area can include numerous dimensions, which can differ from study programme to study programme or institution to institution. The following dimensions, however, can be considered relevant for all study programmes and institutions.

– The physical learning environment concerns the physical infrastructure in which learning processes are taking places, and concerns issues such as health, environment, safety, and others.

– The psychosocial learning environment concerns mostly social relationships, which can take place both physically and digitally. Social relationships are crucial for a good learning environment but can also pose serious challenges when it comes to social exclusion, mobbing or sexual harassment.

– The organizational learning environment concerns (formal) organization of study programmes, administrative systems and structures that relate to learning and well-being.

– The digital learning environment concerns the use and integration of digital learning tools. Their use depends on the specific needs of a study programme.

– The pedagogical learning environment concerns learning outcomes, format and contents of a study programme or course, incl. the various learning-, teaching-, and assessment activities.

-

Quality area: Societal and working life relevance

How does NOKUT define societal and working life relevance?

Societal and working life relevance is in essence about how educational output and society are linked to each other. Societal and working life actors can present important sources in the design of study programmes, depending on the nature and needs of the different study programmes. The concept of relevance, however, can be controversial in that it can be defined differently by scientific and societal actors.

In general, education is considered relevant when it provides both for subject-specific and generic skills. Moreover, it should be versatile in terms of lifelong learning goals, in order to be of relevance for academia’s and society’s future needs (see white paper “Quality Culture in Higher Education” (2016–2017).

Why do societal and working life relevance comprise a quality area?

Input from societal and working life actor is considered an important dimension for higher education institutions. Following central, national policy directives and in order to ensure continuity in systematic quality work, societal and working life has become a quality area at most higher education institutions.

How to work on societal and working life relevance

The white paper on Working Life Relevance from 2020–2021 argues for a more comprehensive and systematic collaboration between higher education and working life. Exchange between academia and society/working life should be considered a mutual relationship, with positive effects for both sides. From an organizational perspective, it is considered effective to establish contacts at study programme level, also in order to ensure regular contact and exchange between the involved actors that are directly involved in the contents of the study programme.

Different study areas have different traditions and needs for seeking exchange with society and working life (for instance professional versus disciplinary programmes). Therefore, depending on the study area, collaboration between institution/study programme and society/working life can be organized differently (e.g., internships, alumni-networks, site-visits, career days, guest lecturers, etc.) and should take into account special disciplinary needs.

-

Quality Area: Learning outcomes

How does NOKUT define learning outcomes?

Learning outcome is what a student is able to do and to understand after finishing a specific learning trajectory. Learning outcomes are formed through different learning and assessment activities, entrance qualifications, and the learning/academic environment. We differentiate between learning outcomes (the students’ actual learning outcome through formal and informal learning) and learning outcome descriptions (a “communication tool” between all involved actors to ensure trust and transparency).

Why do learning outcomes comprise a quality area?

In general, learning outcome is a quality area because of the strong links between how an institution defines and facilitates for learning outcomes, and the quality of its study programmes. A good study programme is expected to ensure that students reach their intended learning outcomes. Learning outcomes descriptions as part of this quality area, have an analytical and communicative function to ensure comparability of learning outcomes across different actors and areas (e.g., lifelong learning, mobility, internationalization and institutional quality work).

How to work on learning outcomes

Systematic work with learning outcomes concerns several dimensions, ranging from provided information on entrance requirements to enhancement activities for the quality of study programmes. Systematic work also includes the continuous assessment of the link between learning activities and learning outcomes descriptions, in order to ensure transparency and trust between students and the institution. In addition, students, peers, working life actors and society in general are considered important external partners in the development of learning outcomes descriptions and study programme evaluations.